Leg Pain and Poor Circulation | Lifestyle Treatments

“Leg pain and poor circulation, called claudication, is the result of the tissue not receiving enough oxygen-rich blood. It is the muscle crying from oxygen starvation,” states Dr. Danine Fruge, MD, ABFP, Medical Director at the Pritikin Longevity Center.

At the time, 1976, Cecil’s surgeon held little hope for his leg pain and poor circulation.

He told Cecil: “I’m sorry, but it’s too late. I can’t help you. You’re plugged up from the middle of your body clear down past your knees. Just go home and take it easy… You have 6 to 12 months to live… I’m sorry.”

But Cecil’s wife, Patricia, had just finished reading about the Pritikin Longevity Center and its success with heart patients. She wondered if cleaning up poor circulation in the legs would have the same benefits as cleaning up poor circulation near the heart.

She wondered right.

Heart-Healthy Food

Cecil flew to Pritikin. He starting eating Pritikin-style – lots of whole or minimally processed plant foods like fruits, vegetables, potatoes, beans, and whole grains. And no foods that would hasten more artery clogging, like full-fat dairy foods and red meat.

And each day, under the strict supervision of Pritikin’s physicians and exercise physiologists, he pushed himself to walk, going as far as he could till the pain was too intense, then resting for a minute or two as the pain subsided, then starting all over again.

Walking Three Miles Daily

At the end of his one-month stay at Pritikin, Cecil’s walking had increased from 100 yards to three full miles a day, and “with just a little leg pain,” he recalls.

Losing 25 Pounds

He had also lost 25 pounds, and had reached a normal-weight range.

Cholesterol Down To 130

What’s more, his total cholesterol had fallen to 130.

Two months after leaving the Pritikin Longevity Center, he started jogging – “real slow, mind you. I’d never get arrested for speeding.”

One year later, he had completed his first marathon, the first of many 10Ks and marathons to come.

Leg Pain and Poor Circulation | Gone

Five years later, researchers at UCLA re-evaluated Cecil. Arteriograms revealed that blood flow in Cecil’s legs had increased from 7% to about 70%. They published their findings in The Physician and Sportsmedicine.1

Collateral Blood Flow

The testing also revealed something that was groundbreaking at the time, the early 1980s. Cecil had developed a vast collateral network of blood vessels in his legs. He had grown, in effect, his own natural bypasses.

What’s more, his femoral (thigh) arteries had dilated (opened up) to enhance blood flow.

Since then, scores of studies have been published affirming the value of a healthy lifestyle like Pritikin in treating peripheral artery disease.

But before we get into the science, let’s back up for some basic facts about leg pain and poor circulation, and peripheral artery disease.

What Is Peripheral Artery Disease?

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is when arteries in the limbs (usually the legs) develop atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is when cholesterol-rich deposits, called plaques, burrow into the inner lining of the arteries. The plaques cause inflammation and injury, and ultimately, blockages in blood flow.

One devastating result of PAD, if left unchecked, is gangrene and amputations.

Having peripheral artery disease also greatly increases your risk of other types of atherosclerotic-related events, such as heart attacks and strokes.

Roughly 8 million Americans have PAD. Disease prevalence increases with age. Currently, PAD afflicts 12 to 20% of Americans age 65 and older.

What Is Claudication?

Claudication is a symptom of peripheral artery disease. It is discomfort or pain in the legs, often described as crampy or throbbing. Symptoms are most common in the calf muscles.

But you may not always feel intense pain. Sometimes it’s just tightness, heaviness, or weakness in one or both of the legs.

Claudication is often referred to as intermittent claudication because the pain comes and goes. You feel it when you walk. It stops when you stop walking.

Muscle That’s “Crying”

“Essentially, claudication is the result of the tissue not receiving enough oxygen-rich blood. It is the muscle crying from oxygen starvation,” states Dr. Danine Fruge, MD, ABFP, Medical Director at the Pritikin Longevity Center.

“Claudication is to the legs what angina

Pritikin Program | Pain Eliminated

In a study2 of 16 men and women with PAD who attended the Pritikin Longevity Center, blood flow to the legs improved dramatically. Pre-Pritikin, the amount of time they could walk was minimal – no more than a few minutes. After one month at Pritikin’s healthy eating and exercise program, they were walking on average two hours each day.

In fact, in 11 of the 16 people, claudication pain was completely eliminated.

Leg Pain and Poor Circulation |

Diabetes

Research has found that having type 2 diabetes triples the risk of peripheral artery disease.3 And the longer you have diabetes, the worse your PAD tends to get.

Getting control of diabetes early on, therefore, may be especially beneficial in staving off peripheral artery disease and its crippling consequences.

With lifestyle changes like heart-healthy eating and regular physical activity, prevention and control of type 2 diabetes can happen quickly, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine found. Following 67 people with the metabolic syndrome, a pre-diabetic condition, the scientists documented4 that within 12 to 15 days of beginning the Pritikin diet and exercise program, blood glucose, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol fell by 10 to 15%, and triglycerides plummeted 36%.

Moreover, 37% of the subjects were able to reverse their diagnosis of metabolic syndrome.

Other studies5 have affirmed the value of the Pritikin Program in significantly reducing blood glucose levels, and for many people, reducing or eliminating the need for diabetes medications.

Leg Pain and Poor Circulation |

Smoking

Many scientists assert that the most important thing people can do to prevent and control PAD is to quit smoking. Research has found that PAD patients who quit smoking are less likely to have limbs amputated or suffer heart attacks or strokes compared to PAD patients who do not quit smoking.6

What’s more, those who quit smoking are much more likely to see improvements in leg pain.

Leg Pain and Poor Circulation |

High Blood Pressure

High blood pressure, especially when combined with other cardiovascular risk factors like smoking and diabetes, increases the chances for PAD.

The good news: Intensive blood pressure control has been shown7 to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in people with peripheral artery disease and type 2 diabetes, and help reduce symptoms like claudication.

Lifestyle improvements can help get blood pressure under control. In a meta-analysis8 of 1,117 people with high blood pressure who adopted the Pritikin lifestyle program, the following results were achieved within three weeks:

- Systolic blood pressure fell on average 9%.

- Diastolic blood pressure fell 9%.

- Of those on hypertension drugs (598 people), 55% left Pritikin free of these drugs, and the majority of the others had their dosages reduced.

So compelling are the data on the effectiveness of healthy lifestyle change in preventing and controlling hypertension that the American Heart Association, among several health organizations, now teaches that a healthy lifestyle is “critical for the prevention of high blood pressure and an indispensable part of managing it.”

Leg Pain and Poor Circulation |

High Cholesterol/High Triglycerides

The National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III9 identified PAD patients as being the highest risk group for future coronary events like heart attacks.

The Panel recommended intensive lowering of lipids (cholesterol and triglyceride levels) to prevent or manage PAD.

Cholesterol- and triglyceride-lowering has also been found10 to reduce claudication pain.

With a healthy lifestyle like Pritikin, cholesterol and triglycerides often fall dramatically. In research11 on more than 4,500 men and women at the Pritikin Center for three weeks, LDL cholesterol levels decreased on average 23%; trigylcerides dropped 33%.

The Benefits Of Exercise

Health organizations like the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association state that structured exercise rehabilitation programs are one of the most effective ways to improve claudication pain.

In a meta-analysis12 of 21 published studies, scientists concluded that PAD exercise programs increased pain-free walking time by 179% and overall walking time by 122%. The greatest benefits occurred when the men and women were exercising five times weekly, and for a total of 30 to 45 minutes.

Certainly, for claudication patients, it hurts to walk. But it is important, under physician supervision, to push through the pain, states exercise researcher James Barnard, PhD, distinguished professor emeritus at UCLA.

In his studies on people with PAD at the Pritikin Longevity Center, Dr. Barnard and colleagues directed the participants to walk to the point of severe leg pain, then sit down and rest, and then, when the pain subsided, get up and walk again.

“This process was repeated until the patient had walked for 45 to 60 minutes.” The rationale for exercising to the point of severe pain was “to stimulate the formation of collateral vessels around the blockage to improve blood flow to the lower leg,” wrote Dr. Barnard in his recently published book Understanding Common Diseases and the Value of the Pritikin Eating and Exercise Program.

“I don’t have leg pain, so aren’t I okay?”

No.

As mentioned earlier, the majority of people with PAD do not have symptoms, but damage is very likely happening within.

In fact, those with symptom-free PAD have a risk of cardiovascular events such as heart attacks that is equal to that of people diagnosed with advanced heart disease.13

And sadly, because symptoms may be nonexistent or mild (many people with leg pain think it’s simply aging or arthritis), many cases of PAD go undiagnosed.

The good news is that diagnosis of PAD does not require expensive, extensive, and invasive testing.

“First, your physician will do something very simple – feel your ankles to check for pulses,” states Dr. Barnard. “If no pulses are felt, your doctor will likely recommend a test called ankle-brachial index.”

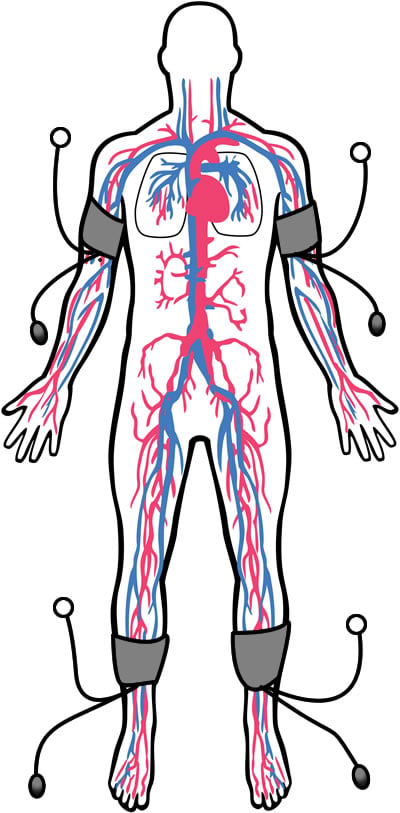

Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI)

Using a Doppler ultrasound device, an ABI takes your systolic blood pressure (the top number) at the ankle and compares it to the systolic blood pressure at your upper arm (brachial) arteries. (see image)

The testing can facilitate early detection of peripheral artery disease and prescriptions for lifestyle strategies like healthy eating and exercise rehabilitation that can help halt the progression of PAD and cardiovascular disease in general.

At the Pritikin Longevity Center, the physicians regularly use the ankle-brachial index test, particularly for people with type 2 diabetes.

“Knowing whether our guests have PAD or not can help enormously in terms of individualizing their care and reducing the risk of heart attacks, strokes, and the worsening of PAD itself,” says Dr. Fruge.

And What About Cecil?

Our high school teacher who was told years ago that he wouldn’t live more than a year because his peripheral artery disease was so bad?

Several years ago, Pritikin Perspective caught up with Cecil over the phone. He was then 83 years old and, he told us, “pretty active!”

He still got on his treadmill every morning for a two-mile brisk walk. He golfed regularly, and had just gotten back from an eight-day cruise to Alaska.

10Ks, Marathons

Over the last four decades, he had competed in 57 10Ks and three marathons. He’d been a regular participant in his region’s Senior Olympics.

Yes, what a joyous phone conversation it was!

Cecil ended it with: “Pritikin saved my life!… And it’s been a great life.”

Sources

- 1 The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 1982; 10 (5): 90.

- 2 Journal of Cardiac Rehabilitation, 1982; 2 (7): 569.

- 3 Circulation, 2004; 110: 738

- 4 The Journal of Cardiometabolic Syndrome, 2006; 1: 308.

- 5 Journal of Applied Physiology, 2005; 98 (1): 3.

- 6 Archives of Internal Medicine, 1999; 159: 337.

- 7 Circulation, 2003; 107: 753.

- 8 Journal of Applied Physiology, 2005; 98 (1): 3.

- 9 Circulation, 2002; 106: 3143.

- 10 Clinical Lipidology, 2012; 7 (2): 141.

- 11 Archives of Internal Medicine, 1991; 151 (7): 1389.

- 12 JAMA, 274: 1995; 975-980.

- 13 Circulation, 2006; 114: 688.